|

| (Mine had neon green zigzags) |

Monty’s bike skidded to a halt in the gravel at the end of the driveway. He glanced back at me from the seat of his hot pink GT, a familiar look of exasperation on his face. “The WD-40 is on the workbench. Hurry up. Jimmy Wallace built a ramp in his driveway.”

I ran into the garage and fetched the can. It was time to roll the boulder up the hill one more time...whatever leaning, ramshackle wedge of lumber remnants Jimmy Wallace had crammed together in his driveway would have to wait.

By summer 1988 I had been skating the same $50 Variflex for three years. At that point, the application of lubricant to bearings was more of a neurotic tic than any sort of real remedy for my board’s eternal lock-ups. The scrap metal spheres rattling around the grooves of my cheap wheels had degraded to the point that they could be considered a real locomotive force only by the broadest and most forgiving mechanical definitions. Nothing ever stopped the seize-ups, especially not wd-40, and deep down I knew it, but I would stick that little red straw in to the wheel and spray away anyway, the cut-rate lubricant pooling so deep that I could have lifted up my wheel and knocked back the ounces of WD 40 like Jack Daniels from a neon shot glass.

Sometimes the WD-40 helped a little. Sometimes

The worst part of it all was, that by the summer of ’88, my blissful ignorance of mainstream skateboarding and “real” skateboards was gone. Any joy gained by skating my disintegrating board was tempered by the inescapable knowledge that my Variflex was shit. Waterhosing my puke green wheels with useless lubricant wasn’t like pouring perfume on the proverbial pig, it was more like spraying Lysol on a vaguely pig shaped pile of manure.

But what else could I do? I had to roll, so I would spray the lube in and ferociously wrench whatever wheel had locked back and forth like a seized up pencil sharpener, gritting my teeth and just hoping for the tiniest bit of circular give, just one crunchy rotation to justify dropping that board down and pushing it around a couple minutes until the next inevitable seize-up.

And Monty was always waiting for me on his bike. That morning, he was less patient than ever.

“Hurry up, Wallace has a ramp in his driveway!”

“I heard you. I’m going as fast as I can!”

To be honest, I felt little urgency in regard to checking out some crappy new “ramp”. I had seen enough bending plywood wedges and two-by-four triangles that summer to be skeptical about anything the kids in my neighborhoods might engineer with their limited knowledge base. Besides, no one could play Evel Knieval with 1/4 of their propulsion system jammed by microscopic bits of the local geology. He’d just have to wait.

After a few minutes, I finally manhandled my wheels into something resembling effective rotation and rolled out into the potholed macadam of Howard subdivision, fully aware that roughly 75 percent of the journey to Jimmy’s would be spent portaging over strips of untenable pavement and intersections choked with gravel. The whole time, Monty, on his infinitely more effective BMX bike, would be yards ahead of me, stopping every 15 seconds or so to let me catch up.

I wasn’t excited about the ramp, but I comforted myself with the thought that there would probably be more guys hanging out there, maybe some kids with boards instead of freestyle bikes. Maybe I could show the crew what I had been hammering away at in Monty’s driveway for most of the morning: my first tentative experiments with the ollie.

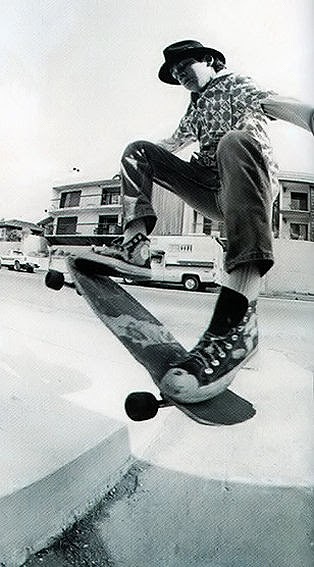

Knowing the ollie existed was mind blowing, but knowing about it before you had access to a decent board was torturous. Even in the embargo days of driveway carving, the concept of jumping off the ground and having the board stay with your feet was something every kid fantasized about. Before the magazines hit our neighborhoods that notion was nothing more than a what-if daydream, kind of like imagining what it would be like if you could ride your bike underwater, or had magic shoes that let you climb up walls. Before seeing pictures of the ollie in a magazine no one I knew really thought bouncing a board off the ground in a skate-version of a BMX bunny-hop was really possible. You could fly above a ramp or momentarily sever yourself from your deck by bouncing a hippy jump, but short of actually fastening your shoes to a board somehow, there was no way to get over even the most minor of obstacles from flat ground.

When we first saw the pictures of the ollie in the magazines, my friends and I didn’t really understand what we were seeing. I was always looking to the peripheries of the pictures for a little curb cut or ramp just off frame, but eventually even backwards wannabes like me couldn’t deny that, yeah, there was a way to jump off the ground and have your board follow you into the air without using your hands. When that daydream crossed the threshold into reality it instantly expanded what skateboarding was, both practically and expressively, in infinite directions. If the coming of the magazines, with their revelations of $100 boards, skate clothes and highly hyped professionals marked a loss of innocence, then discovering the ollie was a return to grace.

|

| WTF!! |

There was a pretty big problem though: all of the pictures my friends and I had seen up to that point, the shots of Natas and Gonz blasting over benches or over schoolyard hips, all captured the ollie at the magic moment of peak flight, that highest-arc split second where rider and board floated through the air without the aid of a ramp or upper body strength. We instantly knew the ollie was the golden gate, the game changer, but those photos, even as they lit our brains with possibilities, gave us absolutely no info on how Gonz, or Vallely or Natas actually got up there.

That day I was pretty sure I had, in my own feeble way, cracked part of the ollie encryption. By reverse engineering the bunny hop, I had figured out that slamming your tail down with your back foot would pop your board vertical and make it stand up on the very tip of the tail. The whole process tipped up the board high enough to just barely raise the trucks and back wheels off the ground. Technically, I wasn’t actually getting the whole board off the ground, I was just tipping up on the tail, but all 4 wheels were leaving the ground simultaneously, and, I thought, if I did the whole thing fast enough, leverage might lift the tail up an infinitesimal bit on the way back down. That would be an ollie right? Sort of? Maybe?

As thrilling as it must have been to watch me clopping my board up and down over and over again in his driveway, my best friend Monty had that new “ramp” at the top of his agenda, sending me into the potholed badlands of Howard Subdivision.

Howard Subdivision was your basic Terre Haute suburb: a cluster of a hundred or so modest, ranch-style homes that spread out in an interstice between the cornfields and patchy woods of Vigo County. The lawns were green, the cars in the driveways were family sedans or stationwagons, and the potholed, gravelly roads were a prospective Thrasher’s worst nightmare. There were no sidewalks. No bus lines into the city, but plenty of access to fallow farm lots, little thickets of wood, and paved driveways.

On paper, Monty’s neighborhood was exactly like mine. It was not the “rich kid’s” neighborhood, there were no gigantic houses, no Beemers or Audis in the driveways. It was a just a simple, boilerplate working-to-middle class enclave, but there was one very important difference: Howard Subdivision, for whatever reason, was a sort of accelerated incubator for suburban fads. In Howard Subdivision, the time honored midwestern tradition of exhibiting affluence via one’s offspring operated at a fever pitch that outstripped anything I noticed on my own block. The kids in Howard Subdivision were not necessarily the most popular kids in school or the richest kids, but their parents made sure they dressed like them. They always had the best Transformers, the newest GI Joes, and, in 1988, the best freestyle bikes. When skateboarding eventually had its boom in Terre Haute, in Monty’s neighborhood, that boom was more like a mushroom cloud. The sheer volume of Canadian Maple circulating there became epic. Freestyle BMX got ditched so fast I am confident to this day that in some thicket surrounding the subdivision there has to be a sort of freestyle elephant graveyard, a place where all those bitchin’ bikes went to die in one mass heap, their chrome-oly frames jutting from the midwestern dirt like fluorescent bones bleaching in the sun.

But I’m getting ahead of the story. Summer ’88 was still in the awkward period after my friends had figured out that skateboarding was about to overtake freestyle BMX, but before any of them had actually gotten their hands on pro boards. Occasionally we heard rumors about a friend of a friend or an older neighborhood kid who had hit the jackpot and got a set up on summer vacation, but almost none of us had actually ridden one of those boards. We all new we wanted a “real” board. Most of us had already picked out EXACTLY what we were going to get from the pictures in the magazines. But that was as far as it went . My friends were still waiting it out on their Haros and GT’s, and I was still trailing behind the neon bicycles on my rotted-out Variflex. There was, however, a palpable tension, especially In Monty’s neighborhood, over who would get a real board first, officially kicking off a whole new conspicuous consumption arms race among the neighborhood families.

So, after some brain-rattling rolling, a few gravel hang-ups and a lot of walking, I was carrying my board up to Jimmy’s house. What I was expecting to see when I got there was another giant plywood doorstop, possibly one sheeted with formica paneling, and most likely leaning at angles that would startle HP Lovecraft.

But something else was waiting for me. Something that would knock my skateboarding ambitions into overdrive like a bicycle kick to the strenum. That ramp I was so skeptical about tuned out to be something more than another Macguyvered cheese wedge. Jimmy Wallace, or his dad, whoever, had built a quarter pipe. A real quarter pipe. 4 feet tall, elliptical transitions, a tiny deck at the top; The kind of ramp The Mess and Hosoi skated in Venice Beach; a ramp you rode up, turned around on and came back down on instead of just flying off the end; you could actually try things like rock and rolls, axle stalls and all the other tricks I pantomimed on the edge of concrete patio steps on it. It had no coping. It was sheeted and templated with particle board, and its position at the side of the driveway meant there was only about ten feet of runway to hit it, but it was a quarter pipe. A real quarter pipe.

And it was beautiful.

When I got there I didn’t even stop to say hi to my friends hanging out in the yard, none of whom looked like they wanted a piece of that ramp. Brent Higgins, who lived on the corner down from Monty’s cul de sac, was sitting on his neon green bike, just watching. Next to him Denny Zigler, future lineman for our high school football team, hulked over his aqua GT, not making even the slightest move toward that ramp. Monty split off from me as soon as he saw those two. Soon, his bike was adding a splash of neon pink to their lurker canvas. None of them wanted to pedal anywhere near the quarter.

They might have been intimidated by the ramp itself, but they were also obviously intimidated by the two headbanger kids lined up opposite the quarter and taking runs. Unlike the polished, over-accesorized neon bikes my friends were on, Their bikes were free of logos, garish stickers, and freestyle accoutrements like pegs and rotors. Compared to the candy colored California confections Monty and my other friends were mounted on, those simple bikes looked like they meant business. The dudes riding them seemed to have a matching temperament. This was good, because it meant they had no interest in picking on the younger kids around them. They didn’t seem to notice us at all.

I took all this in quickly, because I was locked on that quarter pipe. As I walked up, one of the bikers hit it. His mullet trailed out behind him as he accelerated, cranking through the grass of the yard next to Jimmy’s house, an aggro expression on his face. He crossed the concrete slab of the driveway and, in a split second, was shooting up to the lip. With all the momentum he had built he made it to the lip with ease, but when he tried to pull his bike around on the rear tire to come back down the transition, he lost his balance midway and had to plant one of his feet on the plywood. He ended up half-running, one foot on the wood, one on the pedals, down the rest of the ramp, holding on desperately until he was able to to jump off completely at the bottom, both hands still gripping the handle bars, barely keeping upright and in control in his bail.

Turning a bike on a quarter pipe looked really hard.

Next, his friend went at the ramp full blast, but, instead of trying to go up and turn back down, he just aired off the side halfway up the transition and flew out into Jimmy’s yard. It was an OK little launch, but nothing as good as you might get hitting one of the half dozen or so dirt jumps around the neighborhood. In my exhaustively informed 14 year old opinion, Jumping Evel Knieval style kind of defeated the purpose of having a quarter pipe anyway.

Monty had turned his bike into the lawn and pedaled over near Brent and Denny. They had already written off riding, even without taking a single run up the ramp.

All things considered, I probably should have been over there with them.

But Something different had happened to me. When I saw that ramp, it was like a whole new circuit was instantly burnt into my brain, a connection that bypassed all the resistant pathways engineered by years of getting put down and stepped on. This circuit closed and my brain said: “you are going to skate that”. There was no deliberation, no “thinking about it”. The synapses in my brain that controlled doubt and deliberation didn’t fire a solitary dendrite. There was no conscious assertion, There was no whisper in the back of my mind saying: “think about this first”, no voice pondering whether I was ready. There was just no way I wasn’t going to ride that thing and no shred of my psyche held anything resembling a dissenting opinion.

That kind of thing never happened to me. Ever.

It is kind of hard for me to put this moment in the right context. It was not like lightning striking, there was no self-conscious teenage epiphany. It was all so natural. I can only see how momentous it is in retrospect, because now I understand who I was at age 14. Anything I did then was always preceded by a complex calculation of risk vs. reward, and the equation was always heavily biased toward avoiding all risk. I was always asking myself: is this worth failing at? Was it worth maybe getting beat up for? But those calculations just didn’t run that day. Honestly, It wasn’t like I rolled up to a quarter pipe session in Venice Beach and charged in with Hosoi and Jesse Martinez or anything, it was just a neighborhood session on a 5 foot tall quarter pipe in Terre Haute Indiana, but the simple fact that me, the guy always picked last, the guy who had the shit Team Murray when everyone else was rocking Mongooses and GTs, just walked up and put my wheels down and rode that day without any hesitation is kind of a miracle. Everything I know about who I was at that time tells me that it should have never happened. The kid I was should have sat down and watched, he should have kept to the side and played it safe, but for some reason he didn’t. That’s why, when I cast my gaze backwards, that day marks the first moment I can really see how skating, even the paleolithic, pre-pro board driveway phase version of it, was changing me.

|

| What was going down in my brain... |

Of course, actually getting my runs in wasn’t a simple matter of just walking up and putting it down. Those two metal head bikers had to be dealt with. Bigger, faster and older than my crew, they had no interest in bullying or harassing my friends and I, but they weren’t exactly inviting me to queue up into the rotation either. The biggest problem was that, on their bikes, they could start their runs from the grass of the neighbor’s side yard, while I had to come in from the edge of the driveway slab. With their superior mobility they could rotate runs pretty quickly and, although neither of them probably wanted to hit me on the way to the ramp, their bikes would make short work of me if I annoyed them and they decided to take a hit in order to permanently warn me off. I knew timing and inconsequence was the key to riding that day. In short I had to be fast enough to sneak in and sneak out in between their clumsy, but high frequency, attempts to ride the ramp.

So I posted up at the very edge of the driveway, just a few steps back from where the BMXers were crossing in from the grass, watching where they bailed, how their bikes swung when they aborted their attempts. I timed it out. I would have to come in from an angle and carve in a little to get opposite the ramp without getting run over. The timing had to be just right, like jumping platforms in Super Mario, but I could do it, even with blown bearings.

I watched, and watched, and watched...and then pulled the trigger, kicking in behind one of the riders as he came down the ramp, jerkily perp-walking his bike out into the yard, his arms locked in a power struggle with his handle bars. Then it was two pushes, three pushes, right up to the tongue of plywood sticking out onto the concrete at the bottom of the transition. Then I was up, compressed, weight on the tail rotating....

And then gravity pulling me and my board opposite directions. Next, a run out, my Variflex launched off the side of the transition, a spume of Wd-40 trailing behind it as it flew into the grass.

A bail. First try. I didn’t make it. I didn’t care. My attempt was a hell of a lot closer to glory than the struggles of the older BMX kids doing their thing. What was important was that now I knew: This was doable. I could ride this ramp.

After that it was just a matter of dialing in the timing, zipping in while one biker was floundering down and blocking the next guys run. There was no time to think, it was just drop, push, and hit the wood: The rumble of my weight hitting the tranny and flexing the plys, the groan amplified into a dull roar by the hollow, templated design. I bailed a few more attempts, then snuck in again and again until I eventually charged in and just rolled down backwards without attempting to turn, making a “fakie”. I had no time to think about getting my weight wrong and slamming, I was too worried about one of those bikes mowing me down to think about falling.

I kept going for that kickturn, and as I got closer, my adrenaline started to overpower my caution. I started hitting the ramp the split second a bike’s rear tire rolled off the edge of the transition. I was darting in as those BMX guys started pedaling up, just barely avoiding a collision with the incoming riders. When I got my weight distribution dialed, I leaned and pivoted on that tail, and rode down forward, right back the way I came.

When it happened it took a few seconds for it to sink in that I had made it. But, yeah, I had made it. At first I was scared it was some sort of accident, a fluke, so I darted in again as soon as I could. Up, turn, down. This time a little higher, a little less wobbly, then down, the curve of the ramp shooting me back across the driveway and into the grass. Two made. Back to back. Not a fluke.

Now the BMX guys were actually considering me in the rotation. They were giving me a turn. On of the younger kids from the neighborhood picked his Nash up out of the grass, and walked over, eyeballing the ramp, thinking about taking a turn. My friends in the yard rolled up closer on their bikes to watch. It’s a blur from there, because I was going up and back on the quarter every second I could. That afternoon I had to go back home. I knew I wouldn’t be able to skate the thing for another week or two once I was gone. I had to get in every run I could.

At some point the BMX heshers took a breather, and the session turned into a sort of grom feeding frenzy. The grade-school kids who had been hanging back started making their way to the concrete slab. They started circling the driveway, every once and a while inching up the very bottom of the transition and shooting out on the way down. My BMX friends each gave a half-hearted try at the quarter and fared even worse than the big kids, engaging in a few epic run-outs and disastrous entanglements before giving up altogether. Ironically, once the grade schoolers on Nashes and banana boards took over it actually got harder to session the ramp because they were spinning the regular circles on their boards, sometimes butt boarding up the transition. There was no way to account for them, and they weren’t paying any attention to anyone else. I went over to sit among the neon pipework of my friends’ BMX bikes, putting my Variflex into lawn chair mode.

It was at that moment that I got the second hammer blow to my mind state.

Jimmy, the guy whose ramp we had all been skating, finally showed up. He was with another kid named Danny Pike. Danny wasn’t the kind of kid I usually found myself hanging out with during a Saturday driveway session. He was athletic. He was popular. He was handsome. Girls liked him. He was also roughly the size of a third grader. I was a pretty scrawny 14 year old, but Danny was a full head shorter than even me. Despite this, he could have run rings around me or any of my friends in just about any sport anyone might choose. Even at his diminuitive height he had made the basketball team at our Jr. High, spending a season weaving in and out among the throngs of 6 foot tall, glandular cases that made up the average junior high roster in Indiana.

Danny was carrying a very interesting board. I didn’t know Danny was a skater, But I wasn’t surprised. Skating was becoming cool, and this was way before any of us knew that skaters were supposed to be awkward, smelly, outcast punks. At any rate, since Danny wasn’t one of the cool kids who made a hobby out of making my life an exercise in serial humiliation, his presence didn’t register much with me. At least, not until I started really looking at that board.

The first thing I noticed was that his deck just had rails: No nose bone, no tail bone, no lapper. At this point EVERY crap Valterra department store board ALWAYS sported the full range of plastic prophylactics. Not having that stuff was weird. In fact, even from across the yard everything about Danny’s board seemed subtly different. The wheels seemed brighter and differently shaped. The bright pink trucks weren’t just loudly colored, but screamingly bright. Red lights were suddenly flashing in my mind.

That wasn’t a Nash or a Valterra he was carrying.

When they got over to us, Danny started to ask Monty if he could ride his bike, throwing the board aside as he talked.

It landed griptape down in the grass and I saw what the mostly-pristine bottom looked like. An encyclopedic knowledge of skate graphics accumulated by hours of hypnotized absorption of every mag and catalog I could lay hands on went into overdrive. I instantly identified the board from my mental database: Sims Henry Gutierrez. Gullwing trucks. Rat Bones wheels.

I made a few assumptions right away. Danny must have got that set up in the heat of the moment in some shop somewhere, maybe in Florida on vacation, maybe on a trip to Maui And Sons in Indianapolis. It was the deck that gave it away. Henry Gutierrez was a great skater. His Sims board had a cool tattoo inspired skull graphic, right up the preadolescent art conneisseur’s alley, but this was 1988 in Terre Haute Indiana. If you were not a spec obsessed mutant like me the number one pick in the deck draft was something from Powell Peralta. Cab. Lance. Tony, or especially McGill because he had the aggro graphic with the skull and the snake (although you NEVER admitted you bought a board because of the graphic). These guys were the institutionally mandated “best” skaters ever, so if you didn’t obsess over technical crap like me, it followed that their Powell Peralta boards were the best too.

Next in the wish list was probably something from Santa Cruz. Hosoi was on their team at the time, so the rising sun hammerhead with Christ pop-tarting off a launch ramp was an object of envy (my initial pick for a dream board, before Monty snaked me on it...more on that in a later chapter...) Santa Cruz had a deep, deep roster of coveted maple: The Roskopp face, Jason Jesee’s King Neptune and Sun God decks, The Corey O’brien with the skeleton wizard graphic, immortally vibed by Neil Blender in G&S footage. If you factored in Santa Monica Airlines there was the much sought after Natas panther deck. Even before we knew jack shit we knew we wanted to skate like Natas, that and his name spelled backwards was “satan” giving it valuable points in the pissing off your parents and teachers category.

Vision’s offerings were high in the rankings too. The Gator Illusion was the kind of deck girls thought was cool, and, maybe some of that cool would rub off on you. The headache-inducing, saw-railed psycho stick was so radically different from anything we had seen it followed that it must have been better. The classic Vision Mark Gonzales model was heavily scoped, because, like Natas, Gonz was a street king, and we knew when we became hardcore thrashers all we would have would be the streets. The graphic also looked like something hijacked from a Duran Duran album cover, and it was still the 80‘s, so the Gonz’s model was definitely in the running.

But the Sims Henry Gutierrez? The Powells, Visions, Santa Cruzes, those were the trendy sticks, anything else, Dogtown, Alva, Schmitt Stix, Sims...these were certified “real” skateboards, sure, and you’d take one in a heartbeat over your Valterra or Nash, but if you were calling in an order to California for “any deck, any truck, any wheel: $99.95” my breed of suburban hickville wannabe wasn’t going to be picking a Sims Henry Gutierrez. Sorry Henry.

But if they had cajoled their parents into a shop somewhere, and had mom or dad primed to finally buy a complete right then and right there, and that shop was out of Mcgills and Hawks and the Roskopp face, or whatever, That was a different matter. Kids in that situation knew they had to strike while the wallets were hot. Windows of opportunity could close as quickly as the skate shop door hitting you in the ass. Since all the shops we knew about were way out of town there was no “coming back another day” to check for that perfect board. In that context, even for the trendiest prospective skate rat a Sims Gutierrez would do quite nicely.

But here’s the real point: however it had gotten there that Sims Gutierrez was a real fucking set-up. Right there in the grass in front of me, thrown aside like it was a 5 year old hot dogger banana board from K-Mart. A real board. Whose name was on the bottom really didn’t matter.

I sprang to my feet and immediately interrupted the rap Danny was throwing down at Monty “Hey! can I ride your board?”

Danny hardly seemed to notice. “Yeah, sure, whatever.” He said, not even making eye contact.

That was all I needed. I pounced on the board and hit the driveway before Danny had a chance to reconsider.

It was on.

This is beautiful. Love the blog in general.

ReplyDeleteMost commerical and residential snow removal companies rely on a steel plow attached to the front of a pick up truck to remove snow from driveways. This method is safe, quick and efficient and is a cost-savings to both the snow removal company and to the customer.chain link fence cost

ReplyDelete