Outsiders can scoff. It’s easy to think that all I was doing was falling into a fad, but if skateboarding was a fad it was the hardest fad in the history pop culture to actually participate in. Fads are supposed to be easy. Sometimes all you have to do to be in the thick of one is buy some doohickey or scrap of clothing, but with skateboarding, it was a major commitment of time and discipline just to buy your way in. By ’87 Skateboarding was rapidly gaining popularity, sure, but the return wasn’t so much a subcultural rags-to-riches story as it was a rags-to-new-outfit-from-the-goodwill story. Even in throes of Bones Brigade mania, in the midwest becoming a skater was not something that happened unless you really wanted it to. It took a daunting amount of work just to be a poseur. That’s why, even for the trendies who only skitched their way on the thrash bandwagon for a few months, the decision to dabble in skating was a lot more involved than going to the five and dime to buy a hula hoop or a pogo stick, and the effects of that decision had broader impacts. Skaters wax poetic about their first real board. It’s seen as a rite of passage. To an outsider, that’s a corny sentiment at best and a sad overidentification with crass consumerism at worst, but in a time when skateboard shops, sometimes even skateboard magazines, only existed in the major metropolitan areas in the midwest, the simple act of getting your hands on a board was more than an act of consumption, it was a true initiation: a baptism of plywood, urethane and cast aluminum. Here’s your Hosoi hammerhead, welcome to the cult.

To put this all in context. All you need to do is look at another quintessentially 1980’s fad: Breakdancing. Breakdancing is very similar to skateboarding in many important ways. Both activities were created form the grass roots, mostly by urban youths living on the fringes of mainstream culture, both took found cultural objects, whether it was curbs and empty swimming pools or breakbeats on old soul records, and radically deconstructed them for new purposes. Both evolved not only their own aesthetics, but also their own culture, art and even politics. Most crucially, both skateboarding and breakdancing enjoyed a boom period in the 1980’s. There are lots of parallels, but in terms of fads skateboarding could not even compare with breakin’.

For the b-boys who founded the culture in the 70’s it was a long road to prominence, but when Breakdancing and B-Boy culture “made it”, it made it huge. For a while breakdancing was everywhere. It was in commercials, movies, even on the six o’clock news. You could see it in music videos a hundred times a day on MTV. Even in Terre Haute all the chain record stores at the mall were stocked up with Whodini tapes within weeks of the fad going national. You wanted to know about breakin’? Even in my city, a city that pined for the days of segregation and the ascension of the Klan, there were a dozen how to books on store shelves, and breakin’ manuals were available for check out in both the school and public libraries. If breakin’ on down to the bookmobile for a primer on backspins wasn’t enough for you, you could just grab mom and dad’s credit card and dial the 1-800 number you saw in an ad during Thundercats to get Alfonso Ribeira’s Breakin’ And Poppin’ book. UPS would deliver it right to your house, complete with an official breakin’ and poppin cardboard square at no extra charge. Alfonso himself was breakin’ it down every sunday night on Silver Spoons, delivering the streets straight to Ricky Schroeder and the TV tuned American populace. In Terre Haute, the local grocery stores made breakin’ themed birthday cakes, complete with plastic b-boys doing the centipede in sugar frosting. I know this because my best friend Monty had one for his tenth birthday party. His parents rented the indoor pool at the Best Western and we blasted “Wheels Of Steel” and did underwater headspins. There were a half dozen breakdancing movies and, unlike skatesploitation like Thrashin, the breakdancing films played in theaters everywhere and were relatively succesful. They were all pretty corny, but the best of them, Breakin’, was a big enough hit to get 2 sequels.

Breakdancing blew up in a way that made it easy to find out about it and see, but more importantly it was something that could be consumed without participation or even any sort of basic understanding. Breakdancing and b-boy culture slid into a pre-existing cultural mode, it was a permutation of dance, and, as such, was something that could be consumed by watching, by being a fan, even if you never so much as slid a half-assed sock-footed moonwalk across the kitchen linoleum. Elements of the culture slid into fashion and art and music in a way that their origins in the breakdancing culture might not even be acknowledged. How many pairs of parachute pants and half-gloves were sold to kids who had no idea that they were breakdancing fashion? Graffitti art styles infiltrated graphic design in everything from candy wrappers to cartoons, and rap music, its mutation into the mainstream need hardly be mentioned. Even at the height of the craze, being a real B-boy was still really hard, but giving the culture a half-assed shot was fairly simple thanks to its ubiquity. Being a Poseur was absolutely effortless.

Skateboarding, even when it got to the point where there were 3 places to buy boards even in Terre Haute Indiana, was never like that. It has never been a spectator phenomenon, its aesthetic is so obtuse and quirky that it can’t be appreciated by watching it from the outside. Even at the peaks of its cyclic popularity that is always the wall it hits. I’m not claiming that skateboarding is some subtle, intellectual pursuit for some sort of cultural elite. It’s just that skateboarding has nothing to offer those who aren’t willing to get on a board and pay at least a cursory amount of dues and, in skating’s formative years there was always a level of adversity to overcome just to give the art form a try, an element of adversity that had nothing to do with the physical act of actually riding itself. Up until the early 2000‘s even being a wannabe skater required a prodigious amount of effort.

In fact, even in the boom years of the mid 80’s, in the midwest “real” skateboarding was so low key that it had to sneak into our ecosystem like a pathogen: by hitchhiking in on a host organism. It wasn’t Thrasher magazine or even displaced coastal kids that really introduced the next level of skateboarding to my friends and I, it was freestyle BMX and Like any other pathogen, the skate sickness eventually decimated the organism that served as its disease vector.

When the freestyle bikes started showing up in the bike shops, along with their accompanying infrastructure of magazines and industry driven marketing, my peers and I were absolutely salivating for anything that could connect us to the coastal cool lifestyle we knew we couldn’t really have. With their pegs and rotors, and those wildly bent handlebars, Freestyle bikes screamed pacific possibilities in a voice as loud as the neon colors of their paint. You could practically smell the sea breeze wafting off the chrome-oly. Freestyle exploded with a jarring rapidity among my compatriots. One weekend It was me and my best friend Monty pushing our decrepit department store boards around his driveway, and the next I was trying to carve out of the way while he was racking himself trying to pop endos.

The Ironic thing about freestyle BMX was that, even though it had its roots in the dirt-crusted, rural grunginess of BMX racing, it was really an urban and suburban phenomenon just like skateboarding. This meant that, even though those modified BMX bikes were functional on dirt and busted up indiana asphalt, all freestylers really wanted to do was putter around in driveways and parking lots (or if they were particularly adventurous and knowledgeable, on half and quarter pipes). In fact, the BMX mags portrayed skateboarding and Freestyle BMX as intimately linked. Part of this was a logical tip to skating and freestyles mutual inspirations and terrain, but even moreso it was an instrument of marketing, since the freestyle mags were also a major advertising outlet for Skateboard companies. Those magazines, with their intermittent ads for decks and wheels, and their pitches from clothing companies that sponsored Freestylers and skaters like Gotcha or Vision Street Wear, made it seem as if skaters and freestylers shredded in mixed crews, or at the very least, that every freestyler kept a skate setup on the side for fooling around when he or she wasn’t up to riding their bike. The image we saw was one of two California cultures tightly integrated into one movement. This was good for me because it meant ,Even though I was never going to get a glow-in-the-dark bike, there was still a niche for me. I could be the skater in the gang.

Mixing the two activities up during the freestyle bubble made for some strange sessions. A typical Saturday would shake out like this: We’d all start out riding around someone’s driveway, me with my carves and edge grinds, and the rest with their little bunny hops and aborted tail whip attempts. Inevitably, after about a half an hour of fooling around, wherein any attempts at real maneuvers on the bikes would have pretty much devolved into circling around aimlessly and occasionally standing on pegs, someone would propose riding over to someone else’s house. There was no real reason to go anywhere else, the driveways were all pretty much the same everywhere, but since everyone else was on a bike, the urge to just ride off somewhere was always overpowering. So, next everybody would be off on their bikes, and I’d be trailing behind them, hanging up on every pebble on the way, portaging more than rolling, and busting my ass to keep up on my Variflex. We’d get to someone else’s house, and then the whole process would repeat until everyone packed it in altogether and went inside to play video games, or everyone decided to take a marathon ride to the plaza north shopping center a few miles away, in which case I was shit out of luck.

I think, more than the complexity and intricacy of freestyle BMX, it was that fact that you could use your Hot Pink GT for standard pedal pushing like any banana seater that really stymied any progression among my freestylin’ compatriots. It meant there was always another way to slack and delay doing the repetitive, painful work of hammering out those basic BMX moves that got you so enchanted with freestyle BMX in the first place. There was so much aimless riding going on that, eventually, the freestyle bike just became a “bike”. For me, the advantage of this sort of two wheeled ennui was that my friends spent as much time looking at the BMX magazines as riding their BMX bikes, and those magazines, as I’ve already mentioned, had a pretty healthy portion of skate coverage. This was where my friends and I received our first education in what skateboarding really was, or rather, what it could be.

The BMX mags were where I began to see skateboarding not just as a thing to do, but as an invigorating creative pursuit, one constructed on a foundation that I had already grown to love. I was not a wannabe trying to become something cooler or better than what I already was, I was a kid opened up to whole new possibilities, and desperate to take hold of those possibilities. To me, I already was a skater. The flip side to this was that the same images in those mags that were telling me I could find my own place in skateboarding were simultaneously telling me that the board I was riding was crap and what I was doing on it was only skateboarding in the most basic sense.

The importance of just seeing the gear in those ads is hard to convey in today’s context, even harder to convey without sounding like a grumpy old man berating spoiled kids for their “googles and internets”. In 1988, the dissemination of inconsequential cultural information was downright primitive. My generation came to skateboarding at a time before every quirky pocket of American culture was available at a few taps of a keyboard. Obscure datapoints didn’t travel at the speed of fiber optic light, but at the speed of mouth and the US mail. In the midwest, skate knowledge of the most basic kind depended on a world wide web of whispered summer vacation recollections and dog-eared magazines handed down from cousins who lived in major cities.

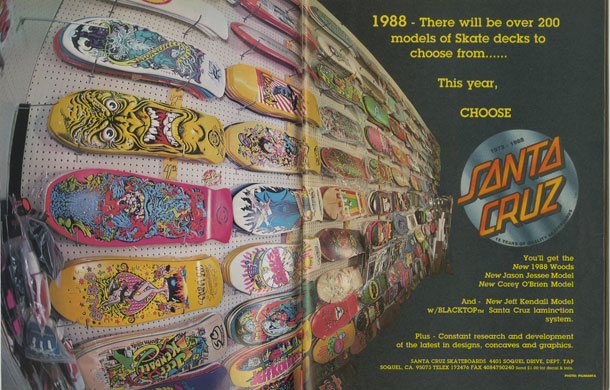

For me, flipping through the pages of Freestylin’ magazine and seeing a skate ad pop up between the pitches for Haro frames and Shimano cranks created a whole new concept of what the skateboard beneath my feet was supposed be. Most important of all were the mail-order shop ads, with their siren songs of “any deck, any truck, any wheel: $89.95”. Before the magazines and the advertisements showed up, there’s was just one way to buy a board in cities like mine. You went to the department store, or pulled out the sears catalog and you picked from a selection of pre-assembled shit; trucks, wheels, griptape, bearings, everything came in one package, and every piece was cheaply manufactured for the mass market by the same fly-by-night Taiwanese manufacturers. The boards all had more or less the same shape, they all had the same array of useless plastic doohickeys attached, and they were all made from the same, unknown to us, sub-standard materials. Your only choice when buying a crap board lied in which graphic to get, and even then the graphics were indifferently conceived and executed by apathetic commercial artists trying to appeal to an amorphous, Dennis-The-Menace demographic. The advent of the Freestyle mags, with their intermittent skate ads, changed all of that. The whole philosophy of just buying a board transformed. Suddenly, There were a dozen different sizes and brands of wheel alone to choose form, with a half dozen or so different durometers . There were various truck brands, all with varying sizes and geometries, you could pick aluminum or plastic baseplates...and the decks, there were a thousand different shapes, lengths, wheelbases (what the fuck was a wheelbase?) tail sizes, nose size (although, in ’88 , they ranged from tiny to nonexistent), concave depths (concave? what?!?) It wasn’t just the idea that you could express yourself by customizing the board, it was that the very existence of so many options implied something conceptually important: that the size of your wheels or the contours of the deck mattered in some practical way. This meant that there were people out there who weren’t pros who were thinking about different things that they could do with a skateboard, and that there were people thinking about how to tailor that equipment to help you ride better. All of these choices implied that there were all sorts of different ways to ride that board, all sorts of styles you could pursue, all sorts of skaters.

Its easy to be cynical and see my starry eyed board envy as a loss of innocence and a testament to adolescent naivete. You could also see it as the most insidious capitalist corruption of a beloved past time. The marketing forces of greedy west coast skateboard conglomerates were reaching into my mind and telling me I couldn’t be a “real” skateboarder unless I bought a bunch of expensive new gear, clothing and stickers. There’s no denying that seeing those ads meant I would never be satisfied with driveway carving and $50 skateboards ever again. The idea of self expression through consumer consumption is anathema to the way most of us see skateboarding, and the insidious subliminal message that you could buy your way into belonging was certainly there in those seductive ads, but there was another even more powerful message being transmitted: A message of diversity and potential. For me Flipping through BMX Action and cherry picking the skate ads was as exciting as flipping through the D&D monster manual had been back in my dice-rolling days. It was an intoxicating blissful sort of information overload. The idea of customizing a skateboard, of individually picking the wheels, the trucks, the deck, separately and then assembling them into something you uniquely conceived was a powerful concept. Make no mistake, those wheels and trucks and beautifully screen-printed decks were mass produced products, inventory made and marketed by companies whose ultimate aim was to make money, but what you did with those parts, what you could assemble with them, was something very personal. The perpetual allure of brightly colored, feverishly marketed, expensive stuff was there and some kids who wound up on skateboards never got over it, but for the kids who would become lifers, or even serious short-term riders, the appeal of individuality, of riding something you chose to put together was even more powerful.

And, of course, there was the actual skating happening in those ads. Hosoi hitting 9 feet on a backside air, Keith meek scraping metal in the post-apocalyptic confines of the nude bowl, and, more than everything else, the rare but tremendously influential street shots: Gonz, Natas, Guerrero....those were the figures who jolted us into a real sort of skate consciousness; the hyperawareness that a good board would turn the world outside of our windows into a proving-ground/playground unparalleled in our youthful experience.

By fall of ’87 my freestyler friends were asking to take my board around their driveways in the midst of our joint sessions with an increasing frequency. I was getting to ride around on their once-coveted day-glo bicycles pretty much at will. By then even I could see the writing on the wall: those kids on their fancy bikes were having what would have been called buyers remorse had any of them actually bought their fancy bikes. They were spending most of their time flipping through the skate ads along with me, assembling hypothetical dream boards and arguing over whether Trackers were better than Indy’s, even though all of us new damn well we had never rode anything but slag metal variflex/valterra trucks. After all, if there is one thing a 14 year old can do better than anything else it’s give opinions on shit they really know nothing about. We’d have extended conversations about the boards we were going to have, just like a bunch of grade school girls meticulously constructing their dream wedding.

“I’m gonna get a Mcgill with trackers and Vision blurr wheels”.

“Vision wheels suck. Those swirly colors make them slow. I read it in the BMX action reviews...”

“I want the Natas but my mom won’t buy it because she thinks it satanic...”

“That Jason Jessee Deck is rad, but he’s not a street skater...I need a street board...”

Seeing the product on the page was really just the beginning of the battle. To appreciate the hurdles kids like me had to hippie jump to get their dream board, you have to cast yourself back to a time before amazon and E-bay, a time when commerce was not connected by ever-present instantaneous data transmission. Today, we entrust our credit card numbers to people we will never see in order to get expensive goods via UPS or US mail as a simple matter of course. In ’87, for the average middle American middle class family mail order was a rare anomaly, and largely the province of either gigantic department stores everyone implicitly trusted or syndicated TV Hucksters like Ron Popeil and the denizens of the home shopping club. You wanted something, you went to the store, looked at it and bought it. Sometimes, if you couldn’t find it in your town, you even drove to another to get it. If you could not get it in the store or the Sears catalog, whatever it was you wanted became automatically suspect. You mail ordered stuff like Boxcar Willie records, pocket fisherman or chia pets, i.e. garbage that wasn’t fit to sit on the store shelves. These $100 skateboards ordered off skull-encrusted ads in these little kiddie magazines...who was to say they weren’t on the same level as comic book x-ray specs and sea monkeys?

And of course, there was the whole logistics of payment. Money orders? Mom or dad had to go to the post office, slap some cash down, send it off in the mail, wait 4-6 weeks...who knew what would happen. Phone orders with a credit card was the best way, but this was not the era of wipe and forget easy credit. The Mastercard only got busted out for emergencies or big items like a new TV or the back-to-school wardrobe. In those days asking for a board meant not only asking for the money, but asking my mom or dad to only unhinge that credit card and call some stranger in California (Where all the weirdos lived) and give them the keys to their credit rating. Sure, $100 was in birthday/christmas price range, but I knew it was still going to take a lot of groundwork to get that board in my hands.

There was some hope though. By the end of 1987 Boards were starting to show up in the pseudo-surf boutique stores that dotted the midwest. Bigger cities always had one or two of these places. They were basically outlets pimping surf t-shirts and fluorescent sunglasses to the throngs of mulletheaded midwestern wannabes who had chronic California-envy. They always had vaguely Haawain, or surf inspired names, like “aloha” or “Surf’s Up”. When skating began to crest in ’87, a lot of these shops started retailing skate gear. A selection of boards gave these shops a whiff of coastal legitimacy. Early on, these retailers, with their stock of trendy beachwear occupying shelves alongside brash skate gear, made for a truly odd, truly midwestern co-mingling of clientele, a sort of cross section of sneering wannabe skaters with preening, wannabe Spaders. The Get Wet chain of stores, which had shops in Fort Wayne and Bloomington had the fringe benefit of being, primarily, swimwear shops, which meant there was a steady stream of women coming in to try on swimsuits while you were milling around with your dirty skate buddies scoping out the latest deck graphics.

When Maui and Sons opened in Indianapolis’ Union Station real skateboard gear gained a middlebrow, Hoosier middle class cache that a thousand Pepsi ads or movie cameos could never hope match. Union Station, for the Hoosier-impaired was an upscale, extremely touristy Indianapolis mall retrofitted from Indy’s old train station. It had nightclubs on the top floor, expensive craft shops, trendy clothing stores, and a big food court, a rarity in the Hoosier state in those days. Union Station had this sort of thin veneer of scenic value by virtue of its restored historic location, making it a honey trap for the status conscious, yet sheltered upper middle class midwesterner. In Terre Haute, where social life orbited around our own mall, another fancier mall in another city actually constituted a hot destination for a special-occasion day-trip. The beauty of having a skate retailer right in the middle of the states prime consumer amusement destination was that, not only could you get your mom and dad to actually see all the stuff you had been begging for, but in Maui they were seeing it in a context that had already loosened their wallets. After all, conspicuous, frivolous consumption was the default status once mom and pop crossed the threshold into Union Station. If you couldn’t get the parental units to lay out 3 figures for a spanking new Roskopp with neon green gullwings and hot pink rat bones, you’d probably at least be able to score a Zog’s Sex Wax shirt or a Vision hip pack.

That corny retail outlet piped more boards into the hands of kids in the Haute than all the other, more hardcore shops like N-Orbit in Indianapolis and DK’s in Kokomo, combined. Throughout fall of ’87 I started hearing the stories at school: near misses of kids who Almost got their dad to get them a complete, friends who SWORE they were going to score a rad set-up the next time they made it to indianapolis to visit their grandma, kids who new some high school kid one neighborhood over who had a new Caballero with trackers and rat bones. A tipping point had been reached, and A grass roots movement was beginning to roll like a swiss bearing. Everyone who came back from spring break beach vacations in ’88 seemed to have a story about browsing in some resort town surf shop and seeing racks and racks of those laminated 7 ply power totems we all coveted. The tales of locals hanging around the shops and what they could do on their boards came with them. The word acid drop entered our vocabulary, and confused, hotly debated accounts of something called the “ollie”. More importantly, there were the telltale signs of a real scene slowly shuddering to life in our neighborhoods: launch ramps seen stashed in strange driveways, a glimpse from the passenger seat window of some high school kid pushing down the sidewalk or approaching the double-sided curbs of Union Hospital.

Everything began to fall into place. For the ambitious wannabes all around me, the parental greasing really began, with every kid lobbying in his own way to get a board, be it through shrill whining or exemplar behavior and contracts on future household manual labor.

Like everyone else, I wanted a real board, but for me the need went deep enough that there was an actual emotional risk in popping the question to my parents. I had a lot invested in the simple desire for a slab of wood with wheels stuck to the bottom, more invested than any well adjusted kid should have. Then again that was the whole point. I wasn’t a very well adjusted kid, despite what my report cards or (lack of a) police record might say. In a lot of ways I had an idyllic childhood: Two parents who loved each other, a nice ranch home in a safe neighborhood, home cooked meals every night around the dining room table with the whole family, but there was a flipside to the baseline normalcy my mom and dad had worked so hard to establish for my family. In the 80‘s especially, Normalcy had its own tidal force, a flow that always shoved and often hammered at any obtuse edge that contradicted its flow. If your were consciously uncomfortable or even merely ignorant of the arcana of the status quo, forces would converge to “correct” you. If you were like me and you were too cowed and sensitive to rebel and become a delinquent then you were merely a loser and a freak, one to be shoved and hammered in that tidal flow for the unforgivable transgression of disrupting the ambient beigeness of the midwestern world.

There had never been a personal pursuit or enthusiasm that I had not been beaten up for, both verbally and physically, mostly by my older brother but also by the omnipresent, pubescent predators that lurked the school hallways like jackals sniffing out any kid who bore the scent of inflicted insecurities. When I developed a love for Spider-Man and The X-men I was a fag for reading comic books. When I was a pre-teen Dungeon master I was a pussy for playing Dungeons and Dragons. I was a nerd for reading the wrong kind of books, a sissy for reading at all. Rich kids, poor burnout kids, the jocks, even the relatively normal kids who needed someone to give shit to just to save face for the shit they took form nastier bullies all took their turns making me miserable. Kids like me, kids who would eventually find a skateboard and hold onto it for dear fucking life, were prey. An outlet for everyone else’s angst. Beating up on a kid like me was another way to confirm their own tenuous place in the ranks of the conformed. It was as much a requirement as Nike shoes or Guess jeans

People talk about how tough it is for a sensitive introverted kid on the schoolyard, but for me the trials didn’t stop when I walked beyond the monkeybars. With my older brother, I had a sort of 24 hour in-house bully service, so the ridicule continued well into after-school snack time and right up to the moment my head hit the pillow at night. My parents did their best to be vigilant, but, the sheer repetitiveness of the emotional and physical pummeling constantly wore away at the retaining wall that separated acceptable, healthy sibling rivalry from actionable, deviant maliciousness. Eventually, the standard was so degraded that nothing short of a serious beating warranted intervention. Meanwhile, they told me all the right things parents are supposed to tell kids with self esteem problems: we love you no matter what. Always be yourself. Sticks and stones... but there was a point where the sympathetic sentiments themselves were not onlt powerless but actually undermining. They became a window into my mom and dad’s own anxieties about me.

My parents knew how hard it was going to be for a kid like me to survive adolescence psychologically intact and they did their best to make it easier, but they often tried to protect me by steering me away from what I was instead of teaching me to embrace it. Despite their most loving intentions they became part of that tidal flow that was either going to drown me or wear me away into grit and nothingness. One year, I had the opportunity to transfer to a special school the county set aside for gifted children. I remember my mom having a sit down talk with me. She told me that she and my dad were worried that being separated form the “normal” kids might be bad for me “socially”. They were worried I wouldn’t “mature” in an environment where I only encountered other children like me. They were doing what they thought was best but what they didn’t think about was the message they were sending: the message that being around smart, bookish, quirky, introverted kids was just going to make me more and more like them, push me farther away from the pubescent mainstream and further into the horrible nether realms of comic books and sci-fi novels. The funny thing is that I was already just like them and I was palpably aware of it: I had the requisite bruises and downward gaze for confirmation. It was like I was being told it would be bad if I became more like myself. It didn’t take a gifted 9 year old to connect those dots. My parents though my trajectory was unhealthy. They were trying to “fix” me. I needed to be steered off the course I was on if I ever wanted to fit in. How they thought several more years of wedgies, name calling, boredom-inducing conventional classes and heart-stopping passing period terror was going to make me better fit in to the social mainstream is one of the greater mysteries of my childhood.

This pseudo-subtle nudging continued into pre-adolescence, a time when growing awkwardness and dawning self awareness combined to multiply the deleterious effects. I had to lobby for years to be allowed to play Dungeons and Dragons. I was deeply into Tolkien, and Conan and movies like The Beastmaster and Jason and The Argonauts, I wanted to write stories like those and with the role playing craze, suddenly there was this crazy game with all the monsters and world building and weird mythology I sought solace in. D&D basically had everything I loved, but this was in the eighties and there had been a tempest in a teacup sized hysteria about D&D and how it drove kids crazy and made them lose touch with reality. Among the millions of kids rolling funny dice at the time, there had been a few troubled adolescents and young adults who had gone off the rails. There had been a few suicides, some other criminal conduct, so when I wanted to explore this new interest there had been another little talk with my mom. This time I was told that I couldn’t spend my birthday loot on Dungeon Masters’ guides and polyhedral dice because I was “just the type of kid who was in danger of taking things too far...” I was older by then, so I knew most of that whole hang up was my mother’s own naivete and susceptibility to Reagan-era media bullshit, but it also hurt in a very real way that my own mother thought I was so far out mentally and emotionally that there was a real chance I might start calling myself Zaktor the sorceror and run off into the night wearing an old bathrobe and shouting incantations. After a period of grudgingly immersing myself in D&D knockoffs like Star Frontiers and Gamma World, they broke down and let me wade into the murky, arcane waters of Dungeons and Dragons but their disdain for the whole pursuit was always evident. What my older brother thought and what he did to “remedy” the situation hardly needs elaboration.

To be fair to my parents I was a weirdo, and I focused on whatever oddball thing I was into at any given time with an intensity and focus that could be startling. Even at the peak of what could best be described as the squirrelly years for most kids, I could go into my room and read Heinlein novels and Marvel Comics for four or five hours straight. If only I could have turned that consuming focus on something practical or socially acceptable my whole life would probably be different. I hated organized sports, girls did not like me. I gave only passing attention to schoolwork, investing real effort only in subjects that caught my interest. I had no clue how to dress or how I should get my haircut. One Year in Jr. high I picked out a pair of girl’s reeboks for my school shoes without realizing it...once school started, of course, I got painful lessons in the gender politics of footwear on a daily basis. Nonetheless, I wasn’t really dysfunctional. I wasn’t what any psychologist or social worker might call a “troubled kid”. I was just a dork. I still had friends I saw almost every day (you had to to play Dungeons and Dragons), I wasn’t dismembering stray cats in the back woods, or carving lines into my forearms with an exacto knife. I wasn’t even the smelly kid in the back of the room eating his own boogers. I was just an awkward, bullied, nerd.

My parents loved me unconditionally, but they were always trying to minimize the impact of what I was. deep down, even my brother loved me, but there’s this cancerous stereotype among the norms that says all dorky kids live in a sort of bubble of cluelessness and that actually just have no idea of the social ramifications of their oddball obsessions. Form this angle, the ranking out and abuse is rationalized as tough love. if you just tell the freaks how out of step they are again and again and again someday they will awake form their fugue and realize how to be like everyone else. The problem with this is that kids like me knew exactly what we were doing. I was much more, and much more painfully, aware of how much I was likely to be ostracized and scrutinized for the things I came to love, but it wasn’t really a choice. If I could have made myself love little league and laps around the gym track, I probably would have, but I couldn’t change who I was, I couldn’t stop loving nerdy books and comics and, eventually, skateboarding no matter waht sort of cost benefit analysis was beten into my be the world at large. Some People, even people whose cruelty springs from what they see as golden intentions never understand this. It’s why they are constantly, and often cruelly reminding kids like i was of how out of step they are; deep down they think they are doing them a public service.

Because of alI of this, I couldn’t just ask mom and dad for a board. There was a danger in rejection that went deeper than anxiety over not being able to get the hot new toy that all my friends wanted. The board would be another referendum on who my parents thought I was becoming. I was in a position where I had to wave the one dog-eared copy of Thrasher I had in front of my mom and dad to try to finagle $89.95 out of them so I could be part of another weird obsession. If they actually somehow took the time to flip through that mag, with its gory Zorlac ads and sketchy photos of sketchier punk bands, there was good chance it was all over. All things considered, my chances might have been better if had had access to Transworld , but i digress. Either way, a judgment was going to come.

The truth was I was holding onto a very personal dream of skateboarding, a dream I had built from the little scraps I had accumulated through years of variflexin’ in the pop culture purgatory of Terre Haute Indiana. My friends and I liked pushing around on our Nashes and Valterras because it was fun, and part of the reason it was fun was that we just assumed anything more than the basics were completely unattainable by kids like us. This meant there was no pressure. We weren’t supernaturally attuned to the expressive, non competitive nature of skating or anything, It was just that nobody new enough about skateboarding to judge anyone. Not knowing how much we sucked was not nearly as important as the fact that we had no way of finding out what was actually good. We just didn’t think about tricks, or building half-pipes or taking our boards into the city streets. We thought somewhere skateboarding was probably a sport with a stifling hierarchy, but for us that was all irrelevant. Competition was irrelevant. Who was best was irrelevant.

The amazing thing was, that when we did learn what was up by seeing those first magazines, when we learned what kids just like us were doing out in the streets and in the backyards on those pro boards that attitude din’t get crushed under the weight of new revelations. That ethos of fun over anything else just got more important. Skateboarding was this space where you made the rules and set the goals. There was a community that pushed you and inspired you but didn’t judge you or rate you or slot you into a formal hierarchy. It didn’t require referees or rulebooks, it had heroes but they weren’t the kid of people you felt were sealed in amber up on a pedestal, symbolizing everything you would never be no matter how hard you worked. On one page of Thrasher you could see button down disciplined geniuses like Rodney Mullen or Tony Hawk, on the next you might see one of the beautiful, wonderful oddballs like Mark Gonzalez or Neil Blender. The page after that you might read about them all thrashing together. They were all skateboarders above anything else. This was not a clique that you needed to be invited into, it was a brotherhood. That was the dream of skateboarding I was chasing. Maybe it was hopelessly, naive. But it was a good dream, the perfect dream for a kid like me.

I’m powersliding into pretention here, and grumpy old man sentiment. Beleive me, I am completely cognizant of how overblown all of this must sound. These words invite judgment but I’m not going to hide behind anything. A lot of what I write in these entries is pretentious, it’s self-aggrandizing. I’m bound to lose even some of the hardcore skaters when I go on like this, because, if you step outside of what we do and look at it with objective eyes, this little past time we love, and this pseudo-spiritual flogging of this kiddie fad shaped like a dead horse is ludicrous. Pathological. Immature. Pointless.

Except it isn’t.

Here’s the only way I can explain it if you don’t understand: Think about the first time your dad pitched you a few underhand throws while you held a baseball bat. Think about what it felt like before you knew there were winners and losers. When all there was was you and dad and you were swinging away and every time you made contact with the ball it was a triumph and every time you missed it was ok because someone wa sthere saying: “try again you’re doing great”. Remember how it was with nobody telling you how many swings you got, no rules telling you you didn’t hit it far enough or you hit it in the wrong direction, no one saying you’ve got to put the bat down and sit in the outfield. Remember Just swinging, missing and hitting? Feeling good when it worked and knowing you could try again as many time as you want when it didn’t, so even missing was fun? You’ve never ridden a board, you can’t figure out what all the fuss is about? Take away the “culture” and the brotherhood and the argument over whether it’s an art or a sport or a stupid fad and that’s it: that’s skateboarding.

This was what was at stake in my simple wish for an $89.95 useless wooden toy. I was a backwards, beaten down 14 year old freak who was afriod that his dream would disintegrate with the wrong answer to one simple question. I was so hung up on orchestrating the perfect context, establishing the perfect conduct on my own part to ensure that I would get the right answer form my parents when I asked that I never actually asked. I was like Ralphie in A Christmas Story, only without the stubborn Chutzpah or charming ingenuity. I dithered and delayed and stuck my head in the magazines and the California Cheap Skates catalog and kept waiting for a “perfect moment”. Anyone who knows anything about life knows there are never any perfect moments.

I liked riding my crappy skateboard. I loved what I was seeing in Thrasher and Freestylin’ but I don’t think I really understood that I loved skateboarding until I finally put my foot on a pro model board for the first time. People talk about transformative moments in their life, and I am aware of how ridiculous it is, in the panorama of life experiences, from births to first kisses to crushing tragedies, to peg that moment as one of those watershed moments, but I’m not going to lie about it to save face. Stepping on an acquaintance’s Sims Henry Guttierez board on a summer afternoon, the first time I ever pushed on a real board, was one of those turning points. I’m betting some of you reading this will know exactly what I am talking about whether you will admit to it or not. What does it say about me, about us, that one of the hundred or so moments I can recall with the nearest thing human memory can approach to crystal clarity is the moment that I set my feet on a legitimate, quality skateboard? It’s pathological. Absolutely Neurotic.

But In the space of that one afternoon, the desire for a new skateboard blasted beyond mere longing and into a full on imperative. After that day, I couldn’t wait for the perfect context anymore. I had no choice but to throw it all on the line and make it happen regardless of the risk. Fate and the world at large was not going to hand it to me.

It was not the last time skateboarding would teach me this lesson.

But How it all went down, and how I finally put my soles on the grip of my very own “real” board, is a story unto itself, a tale of determination, penny ante drama, and a fictional set of siblings known as The Skully Brothers, and it’s also the next story you will see in these virtual pages.

(Continued in part 2)

Nice Blog. Thanks for sharing with us. Keep Sharing!!

ReplyDeleteDo you want to buy Outdoor Touch Screen Totems Online?

Buy Outdoor Touch Screen Totems Online

it is here to get over the Antifreeze coolant from art to get over here for it

ReplyDeleteThe Parking Block Diaries likely explores everyday urban unlimited web hosting lifetime struggles, using parking as a metaphor for life's frustrations and small victories. It offers a humorous or reflective take on modern routines and personal space.

ReplyDelete