There’s great irony in the fact that my friends and I were so clueless about skateboarding in those early days, because, by the mid-80's, mainstream culture had been selling us distorted, monetized visions of the California surf lifestyle for years. Even in elementary school you had to have your OP T-shirt and tacky Hawaiian print jamz to be socially acceptable, and by adolescence we all aspired to be a part of the non-stop buzz and bikini party that was the California life as portrayed by corny sitcoms and a thousand Jeff Spiccoli analogs glimpsed in clandestine viewings of teen-nudie movies on late-night HBO. We all had extensive knowledge of how surfers were supposed to talk, how they were supposed to dress, and (implicitly) what they smoked. We knew surfers were the coolest dudes on the planet, never mind that we knew exactly jack and shit about surfing.

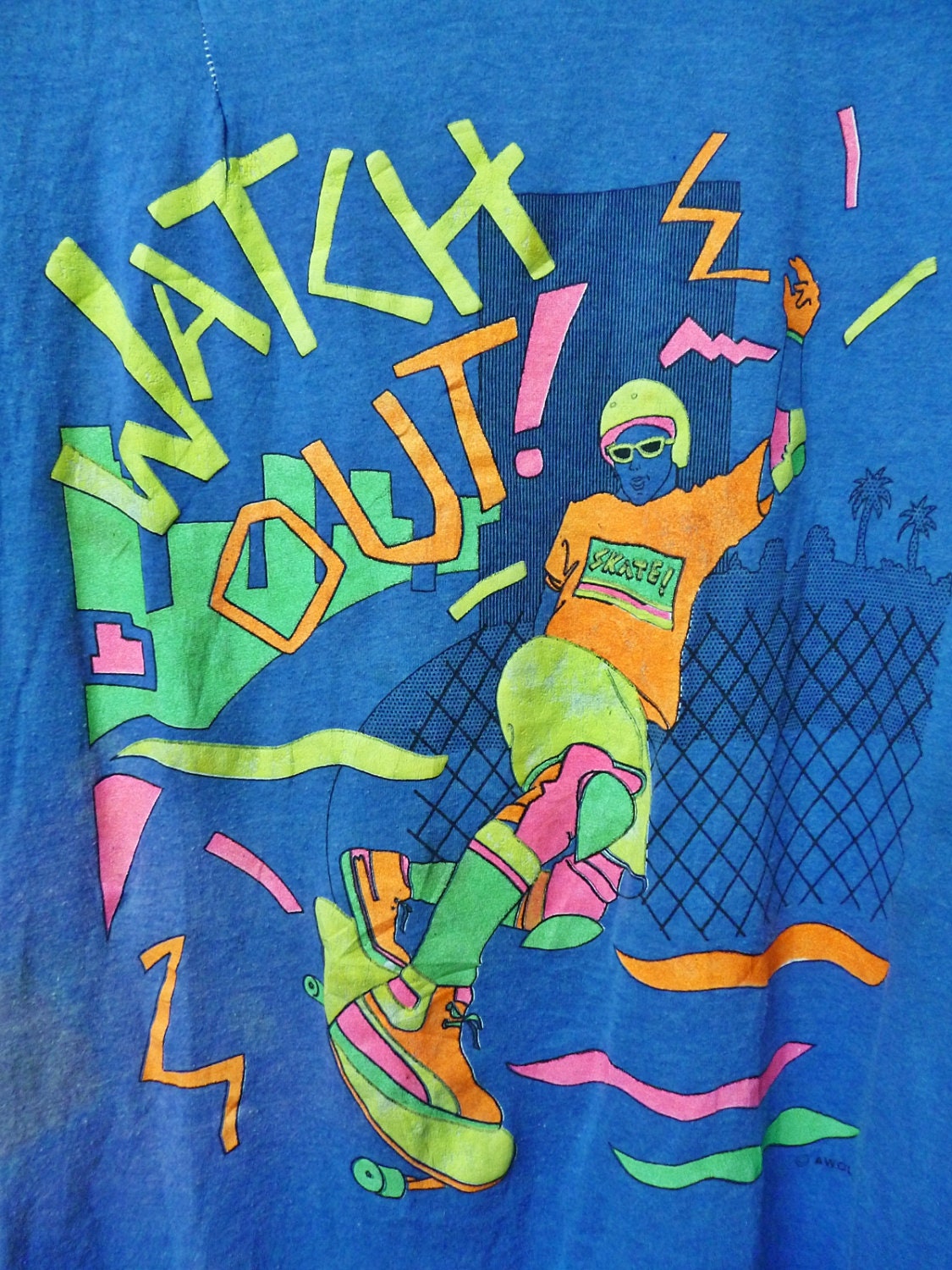

This bastardized awareness of surf culture didn’t really extend to skateboarding. You might get a staticky glimpse of Hosoi doing a giant air on some day-glo pink t-shirt, but the board graphics and faces on those fashion tragedies were always obscured into non-copyright infringing anonymity by a splat of neon paint or some arty screen printing effect. The indecipherable images always had some pseudo-catchphrase like “gettin’ air” or “Totally rad!” plastered across the back as well. The public-domain thrashers on those clothes were never real people, never something you could actually latch onto. At that point skateboarding wasn’t even big enough to be properly regurgitated and re-sold to the rubes in the sticks.

There were also the kids who, through divorce or some other form of parental bad luck, had actually lived in California or Florida but had wound up in the midwest. I can’t imagine what it was like for those poor souls; one day living at ground zero for popular youth culture the next, mom and dad don’t live together anymore (which, as a kid, you knew was your fault) and your packed off to live near grandma and grandpa in fuckin’ Terre Haute Indiana.

They did get the consolation prize of instantly becoming social demigods to us hicks when they got here though. Girls would sit at rapt attention when they spun tales of how much cooler things were where they came from. Boys would make fun of, and be secretly envious of, the clothes they sported and their trendy haircuts. Some of these expatriated kids went with the flow and eventually integrated, becoming bleach blond, slightly hipper hillbillies. Others grew quickly and severely alienated when all the peer adoration metastasized into a cancerous reminder that they were stuck in nowheresville with a cadre of corn country losers who were wildly impressed by the simple novelty of a person who had once lived somewhere better.

Later, some of these exiled kids would become the first disease vectors of a skateboard epidemic. They were the patient zero carriers of a virus transmitted via Hosoi hammerheads tucked away in closets like sad mementos of better days, relics that suddenly reappeared when the next wave of skateboarding hit. To us hoosiers, those guys were like Prometheus bringing fire to the savages. To our parents they were more like settlers bringing smallpox and syphilis to the Indians. A disproportionate number of those tragic transplants I knew would wind up deep into drugs and petty or not-so-petty crime by their high-school years. I think every midwestern skater can think back on at least one of these figures from their life, always with a mix of gratitude and sadness. I can remember two or three from my neighborhoods. None of their stories had happy endings.

Despite all of this, when I finally started really riding that blue banana board It really wasn’t about surf envy. It was just another gimmick in the toybox, another option to fool around with for an hour or so in between games of HORSE and full-tilt Transformer wars. Then, one day, I began to slowly realize the board wasn’t like the pogo stick sitting long-forgotten in the corner of the garage or the Rubiks cube I never came close to solving. I was pulling that board out more and more without consciously acknowledging it.

My neighborhood roads were unskateable, my driveway was crushed gravel, so I’d always have to go to my friend Aaron’s house, board in hand, hoping he would be in the mood to pull out his bright yellow hot-dogger and carve up his family’s pristinely blacktopped driveway with me. There would be a moment of tortured moral dilemma if he wasn’t home when I got there. Was it OK to skate in their driveway when no one was home? I was a real skate anarchist, no doubt. Soon my biggest fear was that all my friends with paved driveways would get bored with skating before I did and I wouldn’t have anywhere to skate at all.

Skateboarding snuck up on a lot of us. Pretty soon you realize you can carve up a 15X30 asphalt rectangle all day without getting bored, maybe you can even spin the occasional 360. Then you could get real bad-ass and get out a couple of old buckets and a broomstick for some hippy-jumps. Next step: a paint-can slalom course. Before you know it you're blindly groping for that next level without even realizing it.

Throughout the whole painful process of taking those first baby steps, there was always the consolation that skateboarding had some sort of cachet by being a part of the beach lifestyle. Surfers did it. You saw it on Hobie t-shirts. It must be cool, right? That's was why, later on, when I got my first glimpses of the animosity peers and adults had toward skating it was so bewildering. The rebel, punk rock attitude of skating, which was already established in the sport’s mainstream, was something we never conceived of when we were hanging ten and butt boarding the driveways. Skateboarding was something from California, and all things coastal were cool. Later on when we did hit the social barriers thrown up in front of anyone seriously pursuing skating, they came out of nowhere. The hypocrisy of the situation snapped us back even harder than it did our California counterparts. Our bad attitudes about the mainstream, the popular kids, crappy pop music, and the cops and fat-gutted hicks yelling “skate or die” out the windows of their rusty trucks came from a real place of confused disappointment. The fuck-you antagonism wasn’t a pose adopted before you even picked up a board. It was the only sane reaction to a world where It was cool to have a skateboarder on your t-shirt but actually being a skateboarder made you a faggot weirdo.

Still, none of that stuff factored in at the very beginning. We were just kids rolling in our driveways and there was nothing threatening about that. A lot of us spent a year, maybe two years carving up driveways before we even knew about the ollie. We clocked serious time on pathetically outdated equipment before seeing so much as a pro-model knock off in the JC Penney catalog. After that we were still usually stuck in Valterra or Nash purgatory for another year or two. It’s sad, but I had been riding skateboards for two years before I even saw a sealed bearing. Those blew my mind. This sad situation laid some serious groundwork for an attitude that still exists in skating’s hinterlands today. It gave what we did a certain flavor when skateboarding got big, and when it inevitably died again, and then got big again. Call it soul, call it stubbornness, whatever. It's still out there today, and if you don’t have it, it doesn’t matter how good you get, because eventually that skill fades away, or never comes at all, and all you’ve got is the feel of the board rolling along. That is the legacy of all those hours invested spinning circles in suburbia.

great read! nailed it with the surf culture slant.

ReplyDelete